There is a debate about films “based on a book”, “based on historical events”, “based on a true story”, based on whatever, if they are accurate or not to the source material, and if they should be accurate to the source they’re based on.

Firstly, movies and books are different mediums. You can watch a movie in two hours, but you can’t do the same with a book. You can complete reading a book in many different hours or days, living your daily life in-between, working, sleeping… watching movies. You can even start a book and then leave it for a while and complete it after a month, but you can’t really do the same with a movie.

An important thing that many people seem to miss, is that there is a certain limitation regarding time in film adaptations of lengthy book stories. If a screenwriter presents a 500-page screenplay taking paragraph after paragraph and chapter after chapter, including every character and every plot, the film will end up to 8–9 hours. For those who are not familiar with it, there is “the 90-to-120-page rule” in the film industry. The suggested film duration is something between an hour-and-a-half to two-hours long, so “the 90-to-120-page rule” means that one page of script roughly equates to one minute of screen time. This is a fact.

A film adaptation is a transfer of a pre-existing work, but what we name a “pre-existing work” can actually be many things. It can be a short or a long story, a book, fiction and non-fiction, comic books (stories and characters), computer games, theatrical plays, mythology and folklore, historical sources and events, true events including journalism and reportage, and autobiographical works.

There is a theory that a filmmaker should be completely unconcerned with the source if he/she wishes to, and the source actually just serves as part of the filmmaker’s vision. A filmmaker doesn’t have any responsibility towards the source material because the story should serve the film. Filmmaking is not a page-to-page translation of a pre-existing work to screen. There are some true stories that might be sensitive, but filmmaking is a form of art, a creative expression, a multidisciplinary artistic work. The film stands on its own, while the source (name it a book, a play, a game, whatever else) is a separate entity and, in film history, there are movie adaptations that weren’t widely accepted because they were different, but there are also countless adaptations that didn’t stay faithful to the source material and nowadays are considered true pieces of art. That happens because a film is a film, and must be viewed and reviewed just as a film, separated from its source and the accuracy or the inaccuracy of the source material. In every form of art, what serves as art’s essence, are its highs and not its lows.

Besides the sensitivity of a few true stories, there is also a debate about the value of accuracy in historical films. Historical films could also educate and protect a cultural inheritance, transporting the audience to different times of history. If a filmmaker wants to make an accurate historical film, there is a need to collaborate with historians and specific consultants, but sometimes, they also need to chose a part, since some historical events can be viewed differently by different countries and scholars. Films such as Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1995), Shekhar Kapur’s Elizabeth (1998), and Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) were completely historically inaccurate but met a huge commercial success, also winning many awards. That happened because other things mostly matter in a film.

A film adaptation can keep the pre-existing work in whole or in part. Depending on the film, the director, the studio, and the targeting audience, a film adaptation can also invent new characters and sub-stories, or delete characters and change the story of the source material. It can also change time and place, even the genre or ethnicity of characters, because a film adaptation is based on the source material, and it is not always a direct and faithful adaptation, since there can be limitations depending on the original source material. Some changes are necessary or unpreventable for a movie, even if there is a will to be a faithful adaptation. For many filmmakers, what’s more important is to keep the spirit of the source material and not every detail, character and plot. Some of them only need particular themes or arcs and expand on them, through their vision, their artistic identity and their own story based on specific elements of the source material.

Technically and typically, when a movie is based, for example, on a book, a film studio and a producer pay for the right to use the source material, so there is a contract between the film executives and the owner of the source material. Depending on the private terms of the contract, the owner of the source material could supervise the context of the material, and the more famous the book or the original story is, the more tricky the final product can be. However, that context is a property for some film executives that is bought, and they can do whatever they want with it. Still, though, the majority of those films have a loose “based on…” tag, which means that the movie doesn’t have to be necessarily a direct transfer of the source material, nor the artistic or commercial success of the film will be based on its accuracy or not. There are other elements that classify the quality of a film.

The script is just one of those elements and one of the main concerns of the writer is to find the cinematic parts of the book or the original story. The main concern is to find, change, expand or transform all those things that will work better on screen, since the different mediums (books and movies) should have a different approach and the better adaptation is not translating paragraph after paragraph the book to a screenplay. A movie based on a book should be easily accessible to an audience that is unfamiliar with the source material, and the writer should focus more on the cinematic storytelling, and character development on screen. However, a quality movie can also be faithful to the source material if it fits the vision of the filmmaker, but there is no rule that a film that is faithful to the source is a better film than one that diverges from the source because The Film Stands On Its Own.

There are countless movies inspired or based on real-life people or events but completely diverge from them as a whole, keeping just specific elements building the movie and a new story around them, creating something timeless. Movies you probably can’t even imagine, like Dirty Harry (1971), Badlands (1973), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986), The Accused (1988), Mississippi Burning (1988), Heat (1995), Almost Famous (2000), and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), just to name a few.

The film industry is so huge, that non-reader viewers of those adaptations outnumber the readers’ fanbase of the original source and those movies stand on their own, something that’s more obvious in major Hollywood productions. A film based on a comic character, or a sci-fi novel, or a fantasy story, will attract the fanbase of this source, but the amount of that fanbase might be negligible in the wider image and the millions of dollars that a blockbuster movie could gain. Of course, each director, producer and film studio needs to live with the consequences of big changes to the source material if we’re talking about regular Hollywood movies, since the artistic vision is not always behind inaccurate adaptations.

10 cases of film adaptations of successful movies diverging from the source material:

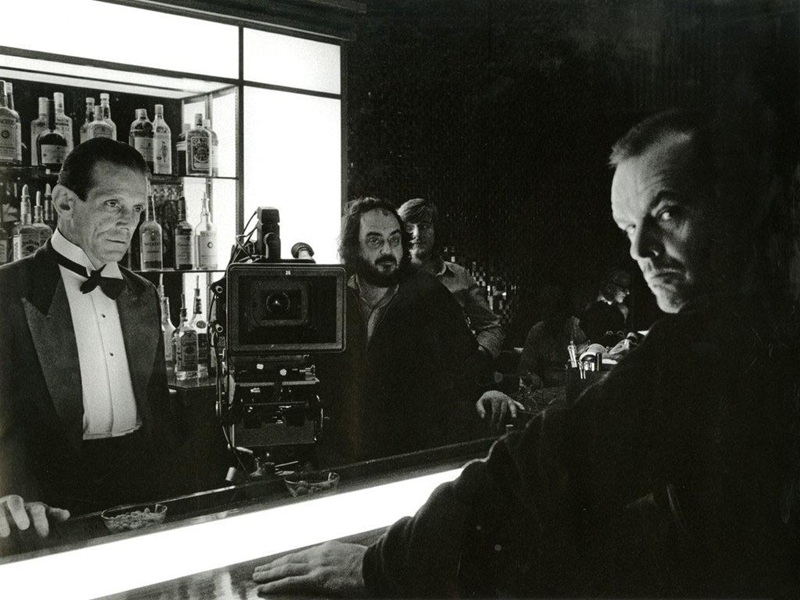

– The Shining (1980, directed by Stanley Kubrick), based on the novel The Shining (1977) by Stephen King.

– First Blood (1982, directed by Ted Kotcheff), based on the novel First Blood (1972) by David Morrell.

– Blade Runner (1982, directed by Ridley Scott), based on the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) by Philip K. Dick.

– Angel Heart (1987, directed by Alan Parker), based on the novel Falling Angel (1978) by William Hjortsberg.

– The Running Man (1987, directed by Paul Michael Glaser), based on the novel The Running Man (1982), written by Stephen King under the pseudonym Richard Bachman.

– Die Hard (1988, directed by John McTiernan), based on the novel Nothing Lasts Forever (1979) by Roderick Thorp.

– Total Recall (1990, directed by Paul Verhoeven), based on the novelette We Can Remember It For You Wholesale (1966) by Philip K. Dick.

– Forrest Gump (1994, directed by Robert Zemeckis), based on the novel Forrest Gump (1986) by Winston Groom.

– Children of Men (2006, directed by Alfonso Cuarón), based on the novel The Children of Men (1992) by P.D. James.

– There Will Be Blood (2007, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson), based on the novel Oil! (1926) by Upton Sinclair.

There are also cases such as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), which is based on Mario Puzo’s crime novel The Godfather (1969). The film’s screenplay is written by the director, Coppola, and also Puzo, who wrote the original novel, but the film has significant changes from the book, even if it involves the same writer.

Bonus film to watch: Adaptation (2002, directed by Spike Jonze, written by Charlie Kaufman), based on the novel The Orchid Thief (1998) by Susan Orlean.